Standing on the steps of the Berkeley Springs castle in the

colorful Fall of 2008, I was approached by several individuals who had just

heard my rambling monologue about the imminent collapse of several banking

institutions and the attendant interventions which would follow. "How are we going to make it through the

collapse?" "What are senior

citizens going to do if their retirements devalue?" As part of his commitment to promoting the

role of foresight planning in public debate, John Petersen and The Arlington

Institute had provided a series of venues for several years in which I

discussed the inevitabilities of the undoing of the Bretton Woods

experiment. Topics like the ECB's

strategy to staunch the bleeding in the Eurozone, the consequence of monetary

policy interventions in the U.S. ,

and the fitful role of China

as producer and consumer were the grist for the Spring Side Chat mill.

Four years ago this weekend, my dear friend and fellow

Arlington Institute board member Napier Collyns laid out a challenge.

"I think it's important that more people be exposed to

what you have to say," he told me in the wake of my lecture.

"What I have to say is not warmly received

anywhere," I replied. "In a

world that wants to avoid dealing with accountability, transparency is not welcome."

"You know what you should do?," he persisted. "You should write a blog!"

A blog? I had no

interest in writing a blog. In October

of 2008, the idea of blogging hadn't crossed my mind for any reason. This, mind you, was not because of my Luddite

tendencies. Blogging wasn’t what it is at present and the means of distributing blog visibility didn't have the social

media utility it enjoys today. So

Napier's request for my blog was, to say the least, unexpected. That my first blog echoes the EXACT same theme

that I have been advocating in the ears of Congressional members and bank

overseers since the Clinton Administration means that:

1. I'm crazy

for maintaining my passionate struggle to link the utility of marginal

productivity back into our financial system;

2. I'm

incapable of presenting it in a compelling manner;

3. It takes a

long time to transform a system that has been 400 years in the making and 100

years in the official dogma of "economists"; or,

4. A bit of all

of the above.

I've been taking considerable time this week reflecting on

the irony that we're quietly marking a centennial that is receiving no

attention. Set in motion with Theodore

Roosevelt and under the leadership of the 27th President of the United States ,

William Howard Taft, an impassioned Congressional inquiry was alight 100 years

ago. During this very month, 100 years

ago, a group in Congress was quite concerned with the lack of transparency in

the nation's banking system and launched a series of inquiries into the

possible ill-effects of consolidating too much national economic policy in the hands

of conflicted private sector interests. Ironically,

the area of greatest opacity to the Pujo Committee 100 years ago is exactly the

same challenge facing our nation and the countries of Europe

today - total ignorance of the actual credits and collateral interest

supporting debt issued by the world's leading financial institutions. From 1905 until 1913, a clarion call for

actual collateral sufficiency (can you hear Basel III echoes?) was resounding

in hearings and inquiries. Opaque shell

corporations (special purpose vehicles) were used to mask assets and liabilities.

Concerned Congressmen were sure that

they were inadequately informed but faced an Executive branch that was delaying the compelling for information disclosure until after the November elections of

1912. Reading the reports of the Committee lead by Louisiana 's own Arsène Paulin Pujo reminds me of the persistent

value of inquiry and the malignancy of secrecy.

However, I feel like I'm in good company with respect to my

self-assessment above as Congressman Pujo was definitely a bit of all 4

conditions I've articulated.

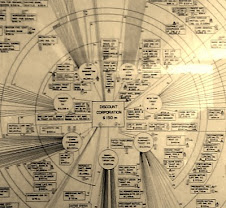

For those of you who don't

recall this part of history, the Pujo Committee concluded that under interlocking directorates and due to common corporate ownership, J.P. Morgan

& Co. and its board controlled 84.9% of the entire market capitalization of

the NYSE. By controlling banks, trust

companies, utilities, industrial manufacturing behemoths, mining, fledgling

telecommunications, and railroads, J.P. Morgan, George R. Baker, and James

Stillman formed a cartel that controlled the U.S.

Rereading the Pujo Committee

Report's 172 pages and the testimony upon which it was written forms the basis

for a rather damning conclusion on the much heralded arguments for transparency

supporting democracy. In depositions and

sworn testimony, then as now, the public was informed of the total control and

collusion wielded by a few individuals acting exclusively for their self-interest

brashly confirmed in their own words and deeds. Then, as now, the public did nothing to avert

the behaviors which would lead to their desperation a few decades later. I read my blog, the Puju Committee report, and

the minutes of today's monetary policy maker meetings and I come to a very

particular conclusion. Being the disseminator

of information - whether you're a Louisiana Congressman 100 years ago or a bald

globe-trotting private sector itinerant today - is of little import unless

people actually consume, and act upon, the information they receive.

The purpose of this blog was

NOT intended to be a monologue. It was

put in motion to be my periodic musings to my dear friend Napier Collyns. It has accomplished that mission as well as

being consumed by several hundred thousand inquiring minds. However, for it to have any effect and consequence,

the next four years will need to have something else: ACTION. This can come in a few forms.

First, it can come in the

form of expanding the conversation to include more people. This is abundantly simple. When you see something worth reading, pass it

along.

Second, and more important, it

can involve a deeper inquiry. InvertedAlchemy

has been constructed not to answer questions but to put context around topics

requiring greater understanding. I would

love to see the comment section of this blog actually appended with commentary

and criticism. It is through this

mechanism that we all would enrich the experience.

And then there's the greatest

challenge of all. Arsène Paulin Pujo

left Congress in 1913 and, following the creation of the Federal Reserve,

largely retired from the fight he had championed in Congress. I'm still running. However, what I know from many of you is that

some of the postings I write are "inaccessible". Since I don't know another language,

particularly when I'm sitting at my weekly scribe table, I'm not sure how to

make what I say more approachable. And

that's where some of you can come in. It

would be amazing to see someone or a group of readers take up the challenge to

write their impressions of what I meant to say. This would do two very important things. First, it could solve the accessibility

issue. But more importantly, as I read

what others say on the same topic, I could adapt my mode of delivery to be more

effective. In the end, we would all

benefit and that, my dear friends, would make a world of difference.

So, here's to the Four Years

Past and here's to Four More Years! Let's

make it a More Perfect Union. Thanks

Napier! I wouldn't have done it without

you.

.jpg)